Arctic Cooperation and the Anarchical Society

The following is an abridged version of an article published in 2021 that addresses many of the geostrategic issues at play today. This article provides vital context to help readers understand current events. It doesn’t advance a specific political point of view and offers a researched perspective that ALL could benefit from. Within the text, you will find updated commentary in RED connecting the analysis to current events. This article does not directly address Greenland’s right to self-determination or its status as an indigenous homeland, as it focuses exclusively on governance structures in which Denmark remains the sole authority determining foreign policy.

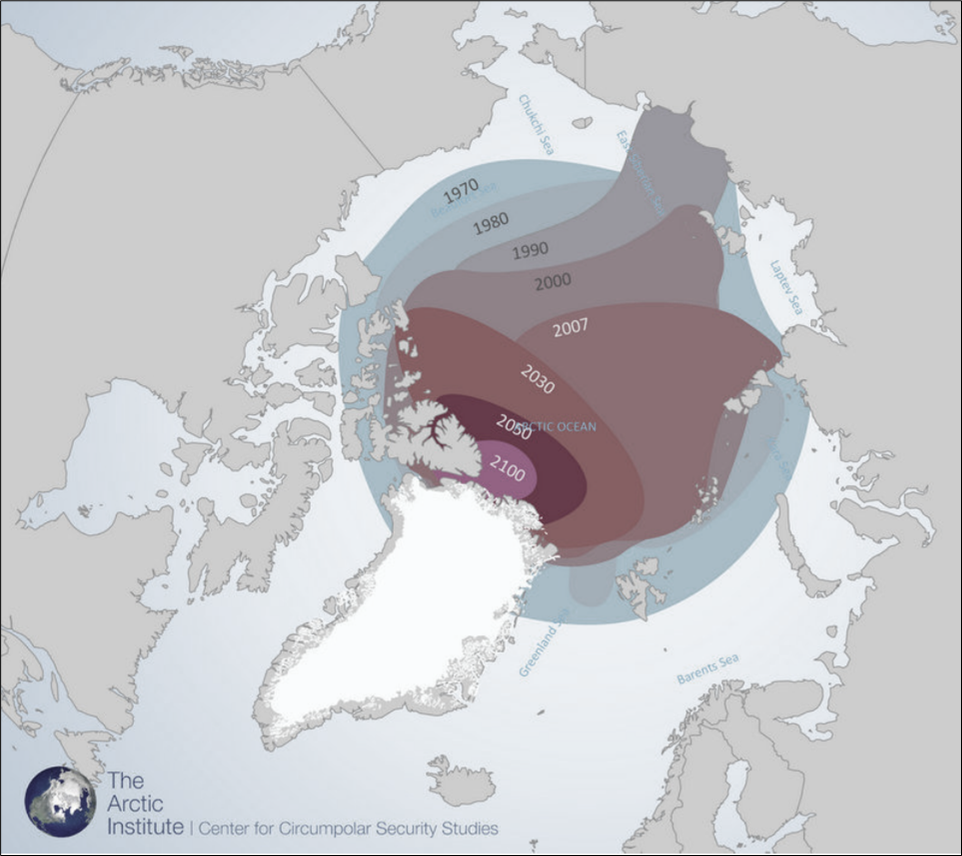

Figure 1: Summer Sea Ice Forecast (The Arctic Institute 2016)

In the warming climate of the early 21st century, the Arctic is being transformed from a perennially frozen expanse of little relevance into a new frontier for a wide array of Arctic and non-Arctic states.[1] If the current trend continues, the Arctic will be largely ice-free for over half of the year by mid-century (see Figure 1). Never before in modern history has an entirely new international waterway suddenly become available, and it’s happening in a globalized age with maritime trade at the forefront.

The emerging opportunities for international shipping and resource extraction have serious geopolitical implications, bringing previously frozen maritime boundary and territorial disputes to the forefront. The 21st century has seen a flurry of activity as states lay claim to areas that were previously considered irrelevant. This rush to determine sovereignty in the Arctic has been exacerbated by an absence of regional governance, long-standing norms, and specific or easily applied international laws. In fact, more treaties govern the behavior of states in outer space and on the surface of the moon than currently govern the Arctic (Spohr 2018). This lack of governance has the potential to lead to conflict as states rush to shore up their national interests in the region; however, thus far cooperation has largely prevailed. Even as tensions rise following U.S President Donald Trump’s threats to unilaterally obtain Greenland by force, at this time, communication is continuing as other states move to de-escalate the situation before actual conflict emerges.

Hedley Bull’s iconic text The Anarchical Society (1977) argues that although the contemporary system of states is anarchical, states are capable of cooperation and orderly behavior through the formation of an international society that prevails in the absence of a higher authority. As the least governed region on Earth, the Arctic is a case study of Bull’s claims. And now comes the ultimate test: Can an anarchical society truly be persistent in the face of instability, or is it doomed to collapse as national interests and raw power take the stage?

ARCTIC MELTDOWN: WHY DOES IT MATTER?

The Arctic has been at the center of conflict before. During the Cold War the superpowers rapidly armed the Arctic tundra and took aim at one another from across the frozen pole. The U.S. and Canadian militaries established an Arctic presence with a string of high-tech, manned radar stations.[2] NATO looked north and built bases in Greenland, Iceland, and Norway, and by the 1980s, Arctic waters were full of Russian submarines lurking below the ice.

Despite the Arctic’s potential as a flash point during the Cold War, it also served as an early forum for cooperation when Gorbachev launched the 1987 Murmansk Initiative to transform the Arctic into an international zone of peace. This speech signaled the thawing of the Cold War by calling for nuclear-free areas, restrictions on naval activities in the Arctic, cooperation on scientific and environmental research, joint development of Arctic resources, and the opening of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) to foreign vessels (Spohr 2018). Although the West was skeptical of regional disarmament, the Murmansk Initiative generated real momentum for scientific cooperation, which ultimately led to the 1991 signing of the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy. This multilateral agreement later grew into the Arctic Council.

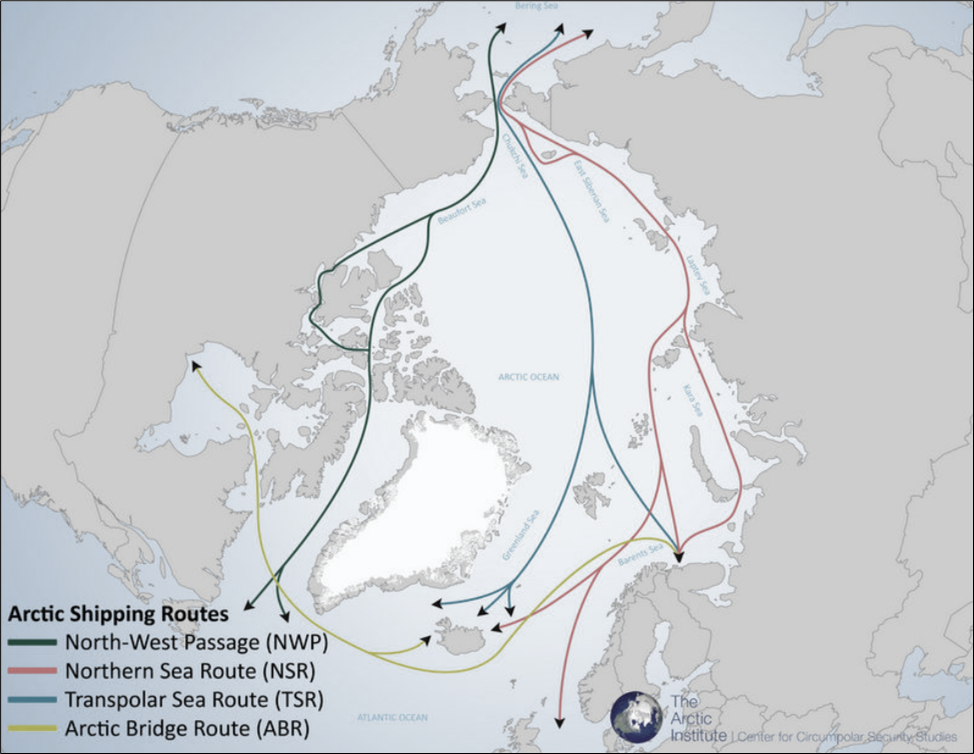

Figure 2: Future Arctic Shipping Routes (The Arctic Institute 2016)

Today the Arctic finds itself in the spotlight once again. The rapid melting of the Arctic ice cap is revealing the maritime highways of the future. The Arctic includes four possible trade routes all of which will become navigable in different time frames (see Figure 2).[3] The one that is most immediately relevant is the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which traverses the Russian Arctic coastline. The second route is the fabled Northwest Passage (NWP), which weaves between the Canadian Archipelago. The third route, and the least navigable at present, is the Transpolar Sea Route (TSR). If the ice cap continues to decrease at its present rate, this route will emerge by mid-century cutting straight across the Arctic Ocean and thereby largely avoiding Canadian and Russian territorial waters.[4] (The Arctic Bridge Route (ABR) is not directly discussed in this article) Although the year-round viability of ice-free Arctic routes remains a dream of the future, stakeholders are already beginning to form long-term strategies to poise themselves to exploit its benefits. For reasons described below, the potential of these emerging routes for both trade and militarization is a significant factor influencing current events.

This push towards the Arctic is driven by three factors:

Ice-free northern shipping routes provide a welcome answer to some of the biggest problems faced by global maritime transport: piracy, instability, and capacity. Maritime piracy is estimated to cost an average of $8 trillion in losses every year, causing shipping insurance through risky routes like the Malacca Strait and the Gulf of Aden to skyrocket. But pirates hardly represent the only risk. The route through the Middle East to the Suez Canal is particularly vulnerable to regional political instability, and the Malacca Strait is controlled by Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, all of whom have had their share of disagreements with China (the primary user of the route and a major Arctic stakeholder). Furthermore, the congested Suez Canal is already operating at maximum capacity, and its dated infrastructure has size restrictions preventing passage of the largest classes of cargo carriers (Blunden 2012). It must be noted that there is serious and well-founded hesitation by many maritime shipping experts cautioning against unrealistic optimism regarding these new Arctic shipping routes. The presence of ice, even with a warming climate, means the use of the routes will be incredibly seasonal and unreliable for many decades, if not a century to come. The NSR and NWP are incredibly difficult and hazardous passages with narrow and shallow waterways, preventing the largest classes of carriers from ever being able to use them. For these reasons, the realistic potential of these routes is OFTEN overstated in the media and by politicians.

The prospective polar routes significantly shorten the distance between several key actors, resulting in tremendous savings of both time and money. In 2009, the first non-Russian commercial vessel, a German transporter owned by Beluga Shipping, successfully used the NSR. Its voyage from Ulsan, South Korea to the major European port in Rotterdam saved 3,000 miles and $300,000 (Blunden 2012). By exploiting the shorter NSR as its primary trade route to Europe, it is estimated that China alone could save up to $60-$120 billion per year in shipping costs and cut its transport time in half (Rainwater 2013). In a world of just-in-time shipping, this is a game-changer.

The existence of vast natural resources in the Arctic presents the opportunity of riches for the littoral states. Although there are still a number of barriers to extraction, such as the difficult Arctic conditions, the prohibitive cost due to presently low global oil prices, and the advanced technology the operation requires, these factors are expected to decrease over time as the ice recedes and technology advances. Since over 85% of the Arctic’s natural resources are estimated to lie offshore, the littoral states (those with an Arctic coastline) have begun to stake their claims to areas previously given little thought in the hopes of striking it rich. It should be noted that most of these resources, particularly in Greenland, remain well out of reach with the costs of extraction and export far exceeding the prospective value of mining.

CUI BONO?

Although eight states have territory north of the Arctic Circle, only five are littoral to the Arctic Ocean – the United States, Canada, Russia, Denmark/Greenland, and Norway. These are the states that will control Arctic shipping routes and have a claim to the Arctic’s natural resources. Additionally, China, as the world’s largest maritime shipper, and the European Union (EU), as the world’s largest trading bloc, are important stakeholders despite being non-Arctic states.

These stakeholders can be broken into three categories based on their broad Arctic strategies.

The Defenders of Sovereignty - Canada and Russia have emerged as defenders of Arctic sovereignty due to their unique geographic position controlling the NWP and NSR, respectively. It is vital to both Canada and Russia that they remain sovereign over their own waterways for security reasons. The internationalization of the NSR and NWP has serious implications that would grant the vessels and aircraft of foreign militaries transit passage rights through waters that both states consider to be internal. Based on these genuine security concerns and the potential to control the most critical Arctic trade routes, the strategies of both Canada and Russia are to preserve and expand their regional sovereignty to the maximum extent possible often through unilateralism. Russia has increased its attention to the Arctic region, elevating it to a second priority in its 2023 Foreign Policy Concept, and has asserted its sovereign claims to the NSR in recent years, issuing occasional threats and interfering with foreign vessels transiting the route. Canada has also recently reasserted its sovereign claims with its 2024 Arctic Foreign Policy.

Advocates of Internationalization - The other littoral states, Norway, Denmark/Greenland, and the U.S., generally agree with Canada and Russia on the importance of sovereignty over the natural resources of the Arctic seabed; however, their official positions on the waterways differ widely. Should Canada and Russia’s claims of waterway sovereignty be upheld, then Norway, Denmark/Greenland, and the U.S. could be effectively denied access to the region and its trade routes. Therefore, it is in these states’ national interest to promote the definition of the waterways as international straits and cooperative multilateralism.

Greenland is strategically positioned between the world’s two largest markets – the EU and the U.S. – and it controls much of the access between the NWP and the Atlantic Ocean. Because of Greenland’s potential as a future shipping hub, Denmark has a significant interest in preserving the right to innocent passage for commercial vessels in Arctic waters.

The United States has been a relatively reluctant Arctic power since the initial burst of interest during the Cold War, but this is starting to change. In 2009, the U.S. released its first Arctic policy, stating: “The United States is an Arctic Nation with broad and fundamental interests in the Arctic Region” (United States 2009). Of key importance is the Bering Strait, which is only 51 miles wide and very shallow, with depths ranging from 98 to 160 ft. This makes it a critical chokepoint for both surface and subsurface vessels wishing to access the Arctic Ocean (United States Navy 2014, 6). As trade in the Arctic begins to increase, any vessel wanting to use an Arctic trade route must pass through the Bering Strait.

Because of the economic and strategic importance of the region, the U.S. has a significant interest in ensuring it will not be denied access. Thus, defining the Arctic as a “global commons” and the waterways as international straits are key components of the overall national strategy. This position was reiterated by the White House in a 2013 statement on Arctic strategy, which declared: “the United States has a national interest in preserving all of the rights, freedoms, and uses of the sea and airspace recognized under international law” (White House 2013, 6). The new 2024 Arctic Strategy reaffirms the U.S. position that Arctic shipping routes are part of a “global commons” that includes freedom of navigation.

The Outsiders - China and the European Union (EU) are regional outsiders with no sovereign claim in the Arctic. These states share the desire for regional internationalization with the U.S., Denmark, and Norway, but, as non-voting members of the Arctic Council, they lack the same tools to pursue this strategy. China has relied heavily on its “Polar Silk Road” strategic policy, which focuses on cooperative bilateral infrastructure investments along future shipping routes in order to gain a regional foothold. They have also increased their cooperation with Russia in the region since Russia controls the NSR, which China hopes to use for future shipping.

Despite China not being an Arctic state, as the world’s largest maritime transporter and energy importer, it stands to reap the greatest benefits from the opening of Arctic shipping routes. Crucially, access to the NSR solves China’s Malacca Dilemma. This dilemma, that a narrow chokepoint dictates China’s global trade patterns and is the sole route for 85% of China’s oil imports, has been at the core of China’s strategic policies for decades.

Beyond the benefit of greater shipping security, the NSR is also economical because it provides a shorter route for all Asian ports north of Hong Kong to reach Europe (see Figure 3). With China being the largest maritime shipper in the world, the opening of this route provides a unique opportunity to deepen its ties with one of its largest trading partners – the EU. Both China and the U.S. benefit from defining the new Arctic shipping routes as part of the “global commons” as this ensures right of access to the region. Since both states advocate for the same regional terms of access, it is difficult for the U.S. to strategically counter China’s claims to the Arctic.

Figure 3: Asia to Europe Shipping Routes (ZME Science 2011)

Like China, the fact that no EU member has an Arctic coastline has not stopped the EU from asserting itself as a regional stakeholder. [5] The EU is the world’s largest trading block and collectively sends or receives 40% of the world’s maritime shipping (Weber and Romanyshyn 2011). As one of China’s largest trading partners, it stands to benefit substantially from the shortened trading route (Blunden 2012). The EU is also the principal destination for many goods and resources extracted from the Arctic. Thus, the EU’s position has been to defend freedom of navigation and promote Arctic regulation and environmental standards.

The 2024 Arctic Strategy proclaimed an official U.S. position of “monitor-and-respond” that prioritizes regional stability and cooperation with our partners along with an intentional approach of avoiding regional escalation of tensions. It acknowledges an “evolving security environment” as the climate changes and Russia and China become more active, but seeks to counter these changing dynamics with a reserved approach focused on monitoring the situation while improving readiness. In recent weeks, however, there has been a dramatic shift in the U.S.’s position.

Incendiary claims by President Trump to “take” Greenland by force if necessary indicate a transformative shift to the way the U.S. positions itself in the Arctic. Importantly, this seems to be a shift from being a staunch Advocate of Internationalization to reimagining the U.S. as a Defender of Sovereignty. This is a shift from prioritizing multilateralism to unilateralism. Should the U.S. “own” Greenland, suddenly it becomes in the state’s best interests to promote the territorialization and enclosure of the Arctic rather than the cooperative internationalization of the region.

Regardless of whether the U.S.’s efforts to acquire Greenland are successful, the attempt itself is likely to have irreparably upset a delicate and long-standing cooperative balance. While it is true that this repositioning may offer more effective countering to China’s claims to the region, this will undoubtedly encourage all littoral states (especially Russia and Canada, who already have strong unilateral incentives) to pivot towards positions of enforced sovereignty over their territorial claims in ways that will have dramatic and lasting consequences for the Arctic region as a whole.

A SYSTEM OF UN-GOVERNANCE

One of the unique facets of the Arctic is the absence of binding governance, treaties, or other forms of international law that specifically address its unique circumstances. This absence of formal governance is what has made the instability of current events possible to begin with. “The Arctic is at issue, above all, because nobody owns it. Unlike Antarctica – governed since 1959 by the Antarctic Treaty, which established the continent as a scientific preserve and banned military activity – the polar region of the north is one of the least regulated places on earth” (Spohr 2018, 23). In the absence of legal instruments like those that regulate state interests in Antarctica, the Arctic is instead governed by soft law and norms (Hunter 2017). These informal norms, however, are not long-standing and, with the rapid pace of change in the region due to climate change, it is unclear whether they still apply. Current events have shown just how fragile international norms can be when even a single party refuses to acknowledge or adhere to them.

The main intergovernmental institution in the region and the primary source of Arctic soft law is the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council was established by the Ottawa Declaration in 1996 to promote cooperation, coordination, and interaction on issues such as sustainability, the environment, indigenous issues, and scientific research. Only the eight states possessing territory within the Arctic Circle are permitted to be full members, though non-Arctic states and institutions may apply for observer status.

Despite the existence of this multilateral institution, the Arctic Council is hardly a sufficient form of regional governance. The reason for this is that the Arctic Council was specifically prohibited at formation from addressing regional security concerns, and therefore it can only address safety, scientific, and environmental issues (Borgerson 2008).[6] Furthermore, the Arctic Council charter empowers it only to make non-binding recommendations on a limited range of topics, based on member consensus and goodwill. Calls to formalize a more robust framework are stillborn, with Russia and Canada reluctant to strengthen it at the possible expense of their sovereignty. Thus, the Arctic Council is a far cry from being able to adjudicate complex geopolitical and security issues, which will likely only increase in importance in the future. This inability to address conflict, militarization, and security, and reliance on consensus, explains why the Arctic Council has little role in these dramatic current events.

The only binding legal instrument that plays a significant role in resolving issues of sovereignty in the Arctic is the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). All Arctic stakeholders, except the United States, are parties to the treaty.[7] The UNCLOS establishes states’ rights and responsibilities for the use of the world’s oceans, and it defines the territorial and economic limits of coastal states. UNCLOS has a number of loopholes and exceptions, which make it particularly difficult to apply to the Arctic without sparking significant disputes among stakeholders.

The ill fit of existing international law to the specific circumstances of the Arctic, combined with the Arctic Council's inability to address issues of geopolitical conflict and security, renders the Arctic effectively devoid of a real governance regime. Despite these shortcomings, all Arctic states have agreed to use the Arctic Council as their main cooperative body as well as to honor the UNCLOS as the primary legal framework to resolve sovereignty disputes.

While not a governing body, NATO also plays an important role in ensuring cooperation in the Arctic. Seven of the eight members of the Arctic Council are NATO members, and this cooperative alliance, particularly Article 5, which enshrines an attack on one as an attack on all, curbs the actions of not only Russia but also China within the region. This alliance enables many Arctic states, including the U.S. until most recently, to support the internationalization or at least cooperation rather than competition in the region. Specifically, when it comes to Greenland, it matters not that Greenland does not have its own navy, since the island is protected by the entirety of the NATO alliance. NATO has also enabled the establishment of military outposts throughout the region, with the U.S. in particular operating bases and monitoring stations across Canada, Greenland, and elsewhere in the Arctic.

Current events seek to throw the current balance into disarray. Should the U.S. gain a sovereign territorial foothold in Greenland, it will rewrite vast swathes of the maritime boundaries in the Arctic, directly threaten Canada’s sovereign claims to the NWP, and shift the current cooperative balance towards rapid territorialization and unilateral securitization.

ARCTIC CONFLICT: AN ISSUE OF SOVEREIGNTY

All areas of conflict in the Arctic center on the issue of sovereignty. But, in a region with no specific treaties, clear international law, or robust governance regime, the way ahead has been decidedly unclear. There are three interrelated issues of sovereignty that the current debate is centered around: waterway sovereignty of critical shipping lanes; territorial sovereignty of undefined maritime boundaries and economic zones (EEZs); and military build-up resulting from areas of contested sovereignty. The current contention by the U.S. falls into the third category as the U.S. seeks to establish new territorial sovereignty at the expense of the sovereignty of Denmark/Greenland. Doing so will have vast implications for both waterway sovereignty and maritime and EEZ boundaries.

When it comes to sovereignty of the waterways, Canada and Russia are the main players and both countries have asserted sovereign claims to their respective shipping routes. Part of the contention is that when the UNCLOS was negotiated, most major international waterway disputes were settled by provisions within the treaty or through bilateral agreements between parties. Since that time, no new major international waterways have emerged. Thus, the advent of entirely new Arctic trade routes was not specifically accounted for, leaving many grey areas of interpretation.

Because of the importance of the NWP, the U.S. eventually signed the 1988 Arctic Cooperation Agreement, pledging that all navigation by U.S. icebreakers within waters claimed by Canada as internal would be undertaken with the consent of the Government of Canada. Despite this agreement, the U.S. has maintained its official position that the NWP and the NSR are international straits requiring the right of transit passage (Lackenbauer and Lalonde 2017; U.S. Department of Defense 2024). This position was made explicit in the 2009 Arctic Region Policy, the 2014 U.S. Navy Arctic Roadmap, and in the most recent 2024 Arctic Strategy. Clearly, this is an issue of high importance to the U.S.

Figure 4: Maritime Jurisdiction and Boundaries in the Arctic Region (Centre for Borders Research 2015)

Territorial sovereignty conflicts are primarily water-based and regard the determination of sovereign mineral rights to the Arctic seabed, which is rich in natural resources (see Figure 4). This scramble began in 2001, when Russia submitted an EEZ extension claim to the UN’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (Borgerson 2008, 63). The debate over oceanic territory reached its climax in 2007 when Russia, using a nuclear-powered submarine, planted a flag on the North Pole’s ocean floor partly in response to its EEZ extension claim not being accepted. Although this act was merely symbolic and carried no international legal status, it provoked a heated response from other Arctic stakeholders.

Notably, the United States is not eligible to file a claim for EEZ extension because it has not ratified the UNCLOS. This has prevented the U.S. from being a significant actor in the territorial carve-up of the Arctic despite having boundary disputes with Canada in the Beaufort Sea and interest in an extended continental shelf (Huebert 2009). There has been a long-standing U.S. intention to accede to the Convention, and a Presidential Directive in 2009 approved the application of UNCLOS terms to resolve border issues concerning the continental shelf in the Arctic. In 2013, the issue was again recognized when the White House stated that, “only by joining the Convention can we maximize legal certainty and best secure international recognition of our sovereign rights with respect to the U.S. extended continental shelf in the Arctic and elsewhere which may hold vast oil, gas, and other resources” (White House 2013, 9). Thus far, however, domestic politics have prevented the U.S. from signing the Convention, and while the U.S. observes the principles of the UNCLOS as customary law, it is still unable to file any legal claims.

Sovereignty disputes over waterways and territory in the Arctic have led to various bouts of militarization in the region. Though the Arctic is no stranger to military buildup, given its Cold War history, the early 21st century has seen a reinvigoration of military activity in the region. In 2008, Canada further asserted its sovereign claim to the NWP by launching a surveillance satellite system designed to detect ships trespassing in its Arctic waters (Borgerson 2008). Canada’s Arctic strategy was formalized in a 2009 report that renewed Canada’s commitment to place boots on the Arctic tundra in alignment with Harper’s “use it or lose it” strategy to defend Canada’s Arctic sovereignty (Lackenbauer and Lalonde 2017). In 2024, Canada released its new Arctic Foreign Policy, which pointed strongly to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine as undermining the stability of the Arctic region and contributing to an increase in regional strategic competition, declaring that “The North American Arctic is no longer free from tension” (Government of Canada, 5).

In 2014, Russia announced its intention to station military units along its Arctic coast, and it began dumping money into infrastructure projects like airfields, ports, and barracks, including the development of two huge complexes (Northern Shamrock and Arctic Trefoil) on islands just 620 miles from the North Pole (Spohr 2018). These intentions were reflected in Russia’s 2015 Marine Doctrine, which outlined its plan to reinvigorate its Arctic naval bases, and in March of that year, Russia conducted a large full-scale military readiness exercise in the Arctic (Conley and Rohloff 2015). Russia is also investing heavily in its Arctic naval fleet by giving its warships icebreaking capabilities, though it should be noted that this is less about Arctic militarization than necessity, as much of Russia’s coastline has sea ice for part of the year (Spohr 2018). Since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s ability to project power into the Arctic has been greatly reduced, forcing a shift towards increased cooperation with China to fund development projects and critical infrastructure along the NSR.

There is also significant concern among the Arctic littoral states about the possibility of Chinese military encroachment in the region. Alfred Thayer Mahan argued that where cargo ships go, warships will follow. Thus, it is not a stretch to imagine a situation in which Chinese naval vessels are in the seas north of Russia, escorting and protecting Chinese merchant ships. Naturally, military bases tend to pop up to secure vital trade routes. If China were to pursue this kind of strategy, it would have serious geopolitical implications and pose a significant security concern to the littoral states (Blunden 2012, 129). China has thus far primarily inserted itself into the Arctic collaboratively with other Arctic nations through investments and infrastructure projects; however, it has been sending more icebreakers and “research” vessels into the Arctic in recent years, indicating growing interest in securing its foothold in the region.

Critically, there are no treaties or international laws governing the militarization of the Arctic, and no existing governance regime or dispute-resolution body to address potential regional conflicts.

THE ARCTIC AS AN ANARCHICAL SOCIETY

Given that there are so many points of regional contention (waterway sovereignty, territorial sovereignty, and militarization), vastly different stakeholder strategies (defenders of sovereignty, advocates of internationalization, and outside interests), and the absence of an adequate governance regime, it is somewhat surprising that there is any cooperation in the Arctic at all. And yet, cooperation has prevailed to such an extent that some diplomats have used the term “Arctic Exceptionalism” to describe the willingness of Arctic stakeholders to set aside geopolitical differences to pursue common regional interests (Spohr 2018). The Arctic’s political development is uniquely characterized by decades of interstate cooperation, the absence of war, and adherence to international law, which has resulted in surprisingly enduring regional stability despite the absence of meaningful governance (Wegge 2011). This evidence is consistent with Bull’s argument that even within an anarchical system, states are capable of cooperation. According to Bull, this cooperation is possible because of the existence of an international order enforced by norms and rules. But can this argument hold?

Beyond promoting the basic goals of society (security against violence, maintenance and fulfillment of promises, stability of possessions), order also preserves the system of the society of states, maintains the sovereignty of the states, and maintains peace. The Arctic Council is the only tangible embodiment of these pillars of order in the region. The littoral states have included respect for sovereignty as a requirement for members and observers, and promises have been made and kept regarding the peaceful resolution of conflict. But, none of this is binding. Arctic stakeholders have made the Arctic Council the primary forum for cooperation and conflict resolution, and yet the Arctic Council cannot officially consider issues of conflict, security, and geopolitics. It has no authority to rule on issues of sovereignty or regional militarization. Even if the mandate of the Arctic Council did change to include these most pressing issues, the rulings are not legally binding, and its decision-making structure is entirely reliant on consensus due to every member having veto power.

States have also promised to abide by the UNCLOS and view it as the primary enforcing rule of the order, but again, this is rife with problems. The root of regional conflict lies in the ambiguous definitions of UNCLOS, which have led to disagreements among stakeholders over the sovereignty of waterways and the ownership of the seabed. Even the rulings of the UN’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf are non-binding and limited to recommendations regarding whether a state’s claim is valid or not.

Thus, the order is hollow and enforced by paper rules, and yet, cooperation has prevailed, and states have consistently adhered to the UNCLOS. Bull identifies three reasons states tend to follow rules and norms: coercion, reciprocity, or self-interest. In the case of the Arctic, coercion is not a valid explanation since no one state has a preponderance of power. Reciprocity may be a component of cooperation, but as the analysis below shows, self-interest is a far more compelling reason for the cooperation that has existed thus far. Simply put, states have cooperated thus far because it suits them. But self-interest is a fickle motivation easily changed by individual whim and the circumstances of the moment.

Russia: Cooperation by Necessity

Despite Russia’s assertions of sovereignty over the NSR, it has engaged in a surprising amount of regional cooperation. Its claims for EEZ extension have been submitted within the framework provided by the UNCLOS, and, despite posturing by planting a flag at the North Pole, Russia has not actually violated any of the UNCLOS rules. In terms of NSR waterway sovereignty, Russia’s assertion of ownership of stretches of the NSR as Internal Waters is thus far within the legal limits established within the UNCLOS, even if the U.S. and other parties disagree. Russia has also cooperated with other states bilaterally to peacefully resolve maritime boundary issues with its neighbors, the U.S. and Norway.

Based on Russia’s track record, and despite periodic bouts of military posturing, Russia has so far demonstrated a willingness to cooperate. However, the willingness to cooperate within the Arctic Council seems to have disintegrated following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

So, why has there been so much cooperation, given that Russia’s overall Arctic strategy is one of aggressive sovereignty? Russia’s drive to cooperate is not altruistic or in the spirit of liberal internationalism. Russia suffers from a weak economy and lags behind in technological advancements. Resource extraction in the Arctic can be prohibitively expensive and requires cutting-edge equipment and infrastructure. Therefore, Russia’s regional cooperation is motivated by a need to share advanced technologies and costs. This reason for cooperation has prevailed even in undisputed Russian territory, where the Norwegian company Statoil has been awarded a 25% share in the profits of oil exploration because it was the only company with the technology for drilling and extraction (Piskunova 2010). Similar patterns of instrumental cooperation are ongoing and increasing with China for the same reasons. Thus, for now, cooperation is a necessity for Russia to pursue its regional economic interests. Even if Russia has not proactively cooperated within the Arctic Council in recent years, it has not actually shifted to a more aggressive posture in the Arctic region and remains focused on more immediate concerns domestically and in Ukraine. This confirms Bull’s argument that states will often comply with the rules and norms of the order because they find it is in their own interest to do so.

China: Cooperation as a Foothold

Necessity is also the primary motivation of China’s Arctic cooperation. China recognizes its geographic disadvantage as a non-Arctic state, yet it is actively seeking a foothold in the region. This privileges the projection of soft power and cooperation over confrontation. The result of this has been a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, China is an enthusiastic participant in the existing multilateral Arctic institutions and a leading innovator in Arctic scientific diplomacy. It was admitted as an observer to the Arctic Council in 2013 and established a permanent Arctic research station in Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago in 2004. These moves effectively granted China access to the polar club despite being an outsider (Rainwater 2013).

On the other hand, China is aggressively pursuing bilateral investment opportunities with Arctic states like Russia, Norway, Iceland, and Greenland, which will provide it a gateway to shipping routes and a stake in resource extraction to which China would otherwise have no claim. This is a mutually beneficial cooperative strategy, at least for the short-term. The development of required infrastructure (deep sea ports, supply stations, long-distance railways and roads, and undersea fiberoptic cable networks) to support the NSR is a monumental undertaking, and Russia lacks the technology and finances to do it alone. Thus, the Russia-China partnership is mutually beneficial, advancing both Russia’s need for capital and China’s desire for an Arctic foothold.

China has also made great efforts to cooperate with and invest in other Arctic states. China has had bilateral talks with Norway, and Norway was also a strong supporter of China’s application for observer status to the Arctic Council. Denmark has also voiced support for China due to its interest in developing Greenland's natural resources, which would otherwise lack the capacity to develop and extract them on its own (Rainwater 2013). China views Iceland as a key future partner due to its strategic location and deep fjords, which make it an ideal shipping hub for Chinese goods (Blunden 2012). This cooperation between China and Iceland even led to the signing of a free trade agreement in 2013, and the new Chinese embassy in Reykjavik is the largest one in the country (Spohr 2018).

Thus, China’s actions have stressed bilateral cooperation and active participation in the Arctic Council and China has still consistently chosen cooperation over conflict (Rainwater 2013). This is because the two-pronged cooperative approach results in bilateral agreements that secure strategic interests while also engaging in cooperative institutional and legal efforts that allow China to potentially influence the interpretation of the waterways as international straits. Therefore, China has also found cooperation to be within its own interest. To date, there has been no change in China’s overarching strategy to influence the region. Their strategic interest in the Arctic is legitimate, and though some states, like the U.S., perceive their efforts as an encroachment (and it very well may be), it must be acknowledged that cooperation has been the operating framework thus far.

The U.S.: A Cooperative Dilemma

The area in which U.S. cooperation has really shone is scientific research, but cooperation in other areas of policy has not been so simple. The U.S. is in a very tight spot when it comes to waterway sovereignty. On the one hand, the U.S. has an important interest in sections of the NSR being declared an international strait. International waterways grant the right of transit passage to surface vessels, subsurface vessels, and aircraft including those of foreign militaries. If the NSR is declared an international waterway, the U.S. military cannot be denied access to strategic straits immediately off Russia’s coast.

On the other hand, the U.S. also has a strategic interest in preventing Russia from obtaining those same transit passage rights through the NWP. If the NWP was designated an international strait, “anyone, including the Russians, would have the right to fly their military aircraft over the waters of the Northwest Passage — clearly, such a right would not be in the security interests of either Canada or the United States” (Huebert 2009, 21).

Because of this “darned if you do, darned if you don’t” strategic conundrum, what has emerged is a policy position that declares both the NWP and NSR as international straits, while maintaining the 1988 Arctic Water Cooperation Agreement that acknowledges Canada’s sovereignty of the NWP (Huebert 2009). This political “fence riding” recognizes Canada’s sovereignty in practice while asserting internationalization in principle. Therefore, the U.S. is in a cooperative dilemma, both unable to challenge waterway sovereignty legally or to accept it publicly.

This cooperative dilemma is shifting dramatically now as the U.S., under President Trump, moves toward a more realpolitik approach to regional strategic balancing. Today, rather than emphasizing the internationalization of the region, which has guaranteed the U.S. access for centuries, it has adopted a “what’s mine is mine, and what’s yours should be mine” approach, which is likely to set off a cascade of events redrawing maritime boundaries and forever changing the region once known for its Arctic Exceptionalism.

Denmark: Cooperation for Greenlandic Development

Denmark is a unique case. The country itself is not an Arctic nation, but because of its association with Greenland, Denmark maintains a seat at the Arctic Council and a voice in the region. Denmark has been proactively cooperating on its extended EEZ claim, which overlaps large areas with Canada's and Russia’s claims. Pituffik (Thule) Air Base represents long-standing U.S. defense cooperation, and both NATO and the 1951 Defense of Greenland Treaty with the U.S. guarantee protection of Greenland’s sovereignty.

Greenland is rich in natural and mineral resources, but there is very little infrastructure, and it simply does not have the capacity to develop them alone. This has generated a lot of attention from non-Arctic stakeholders like the EU and China, who are looking for a regional foothold. The 2011 Arctic strategy set clear targets to attract foreign investors to “ensure the exploitation of Greenland’s natural resources in the future will constitute a major source of revenue for the Greenland society” (33). However, this strategy may have proven to be more of an invitation to non-Arctic actors, such as China, than was originally intended, and China has made extensive efforts to invest in infrastructure development projects, such as upgrading Greenland’s airports. Ultimately, these efforts to invest in critical infrastructure were thwarted following an intense pressure campaign by the U.S., but it highlighted some of the risks associated with welcoming investment from outside sources. In more recent years, Denmark and Greenland have both been more selective about which companies are permitted to invest and develop within the island territory. Even so, Denmark’s motivation to cooperate within the existing regional framework appears to be centered on attracting necessary investment for resource extraction and infrastructure development while enjoying some outsized regional influence in the Arctic Council that the small state does not garner in other international forums.

Canada: Cooperation Suits Them

Of all the stakeholders, Canada has the least incentive to cooperate. With an advanced Arctic fleet, a capable military, advanced technology, a strong economy, and de facto sovereignty of the NWP, Canada has every reason to maintain its position of strength among the Arctic powers. Among the Arctic states, Canada has been the most aggressive and militaristic, repeatedly interpreting the actions of other states, particularly Russia and the U.S., as hostile. Despite several tense moments in U.S.-Canadian Arctic relations, both parties have generally been willing to cooperate bilaterally on important topics, as the 1988 Arctic Water Cooperation Agreement demonstrates.

Due to Canada’s position of strength, the most compelling explanation for its cooperation thus far is a combination of recognizing the importance of its relationship with the U.S. and understanding that regional instability does not suit its own long-term interests. As such, cooperation is the best path to maintain peace, and therefore it currently suits Canada’s own self-interests.

The many shortcomings of the existing governance structure have already been discussed, but a weak regional governance structure that permits the Arctic states to pursue their own agendas while keeping outsiders at arm’s length is precisely what the Arctic states (especially Canada, the U.S., and Russia) prefer. This is regional cooperation that reflects self-interested state preferences in which their sovereignty is preserved and regional economic interests are protected from encroachment by non-Arctic stakeholders. Thus, the existing system is weak because many Arctic states prefer it this way, as it allows them a wide degree of latitude to pursue their own regional interests.

A FRAGILE ARCTIC PEACE

This article has established the existence of anarchy in the Arctic region. There exists no higher authority than the states and there is no regional governance structure capable of restricting state actions. Despite this anarchy, however, it has been shown that all Arctic stakeholders do cooperate and they generally behave in an orderly manner. In fact, they cooperate to such an extent that the Arctic region is characterized by a surprising amount of regional stability featuring cooperation even at times of tension as its most defining characteristic.

This society, however, is fragile. As the evidence shows, states do cooperate; however, the analysis above indicates that the primary motivation for this cooperation is because states perceive cooperation to be in their own interest. Self-interest is not a robust endorsement for long-term peace in the Arctic since many of the drivers of cooperation in the region are transient. The Arctic is a rapidly changing environment. States like Russia and Greenland have weak economies and are hungry for foreign investment in infrastructure development projects. This is being done bilaterally, predominantly with China, which is often perceived as a hostile encroachment by the U.S. Most importantly, it is easy for states to cooperate now, while the feasibility of Arctic shipping highways remains a dream for the future. And don’t forget the wild card. The Arctic is a unique region, but it is not immune to spillover from geopolitical conflicts elsewhere. Without any agreements to prevent militarization, there is little that could prevent a return to the past.

In the absence of adequate regional governance, it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which the current level of cooperation continues. The Arctic is likely at a critical juncture. As it currently stands, it is within most states’ interests to cooperate in the region. But as the stakes increase, “the potential gain of unilateral defection will outweigh the gains reached by cooperation” (Jervis 1978). Without a strong Arctic governance regime in place to ensure promises are kept, it is probable that the cooperation of Bull’s anarchical society will breakdown as states fall into a classic security dilemma.

And with that final comment, here we are. I find myself in a position to be right, even when I wish I were not. The signs of a breakdown have been showing for some time; however, I don’t think anyone could have truly predicted that it would be such a spectacular rupture to the existing cooperative regional order. As the 2024 Canadian Arctic Foreign Policy wrote, “The guardrails that we have depended on to prevent and resolve conflict have weakened” (2). And now, I fear, they may have collapsed entirely.

This article provides critical context to help understand why things have fallen apart the way they have. The Anarchical Society is real, but perhaps it was always liminal and doomed to fail. In a region absent of robust governance, the self-interest of states to cooperate has proven to be fickle and unreliable, causing the security dilemma of great powers to take over. And yet, conflict is still just beyond the horizon… like a mirage. We can see it’s a possibility, but it hasn’t yet materialized. For now, countries are talking, debating, and posturing - this is still a form of cooperation, even if it isn’t the friendliest version of it. The time to worry will be when the conversations stop, when the discourse falls silent. As long as talking is happening, a solution can be reached.

The U.S.’s strategic interests are genuine and not new (I can expand on this later in other posts), but our partnerships with Greenland, Denmark, and NATO are longstanding. Reaching a resolution for increased defense of Greenland is, in reality, in the interests of all NATO member Arctic states and in the interests of Greenland as well. However, increasing security by upsetting the region's delicate balance of sovereignty would have tremendous costs.

We are at a fragile inflection point - the critical juncture I forecast back in 2021. The consequences of lingering at this juncture are severe. Should the U.S. move to violate the sovereignty of another Arctic state, several things will happen. NATO will instantly dissolve with repercussions that will ripple around the world in ways we can’t even dream of yet. The delicate balance maintaining cooperation in the Arctic will tip towards rapid territorialization, securitization, and sovereignty assertions. International waterways will be closed off, Russia will be left with no choice but to seize anything it can, and China will be emboldened to act unilaterally to secure its interests in its own waters. This will be a self-own of a kind that will fill whole chapters in future history books.

The cracks in Arctic cooperation were showing long before this recent chaotic episode. However, one must wonder what damage will be done even if a resolution to the current crisis is reached? Will the Arctic ever be described as a region of peace again? And what signal does it send to both our allies and our adversaries when the U.S. asserts that might makes right on the international stage? Our international system in the Arctic and beyond has long been upheld by norms, rules, and soft power. Should the collaborative norms of the Arctic collapse, the implications are likely to radiate throughout the international system, forcing a realignment of power and the formation of an entirely new world order.

Here we stand in the interregnum - the space between what once was and what will be. It’s a perilous moment where all nations have a choice to make about what kind of future world they wish to create.

[1] An open water vessel is one which lacks any additional hull reinforcements or ice capabilities traditionally required for Arctic sailing.

[2] During the Cold War, the Canadian federal government also relocated a number of indigenous families to small communities in the High Arctic and instituted programs which drew nomadic indigenous peoples into strategically placed government housing villages to bolster claims of territorial sovereignty (Lackenbauer and Lalonde 2017, 128). These controversial moves resulted in Canada later making restitution payments to the families of those who were relocated and Canada eventually issues a formal apology.

[3] Figure 2 also depicts the Arctic Bridge Route (ABR) which is not discussed in this paper.

[4] Though entry and exit to the Arctic Ocean to access the TSR would still require passage through the territorial waters of the Bering Strait controlled by the U.S. and Russia, this strait is designated as an international waterway under the criteria of the UNCLOS.

[5] Although Greenland is an autonomous territory of EU member Denmark, Greenland left the EU in 1985. Though the EU is Greenland’s primary trading partner and there are some association agreements between them, the EU exercises little to no influence on Greenland’s policies as it pertains to the Arctic. Furthermore, EU members Finland and Sweden are members of the Arctic Council but lack strategic access to the Arctic Ocean.

[6] The U.S. demanded a footnote be placed in the charter which reads “The Arctic Council should not deal with matters related to military security.”

[7] Despite not being a party to UNCLOS, the U.S. views it as customary international law and practices adherence.

Bibliography

Blunden, Margaret. 2012. "Geopolitics and the Northern Sea Route." International Affairs 88 (1): 115-129.

Borgerson, Scott G. 2008. "Arctic Meltdown: The Economics and Security Implications of Global Warming." Foreign Affairs 87 (2): 63-77.

Bull, Hedley. 1977. The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Centre for Borders Research. 2015. "Maritime Jurisdiction and Boundaries in the Arctic Region." August 15. Accessed November 25, 2018. https://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/ibru/resources/Arcticmap04-08-15.pdf.

Conley, Heather A., and Caroline Rohloff. 2015. The New Ice Curtain: Russia's Strategic Research to the Arctic. Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

Cros, Laurence. 2018. Canada's Straight Baselines. February 7. Accessed November 29, 2018. http://option.canada.pagesperso-orange.fr/NWP_baselines.htm.

European Commission. 2008. The European Union and the Arctic Region. Brussels: European Union.

European Parliament. 2008. Resolution on Arctic Governance. Brussels: European Union.

Futures, Geopolitical. 2017. Major Choke Points in the Persian Gulf and East Asia. April 17. Accessed November 25, 2018. https://geopoliticalfutures.com/major-choke-points-persian-gulf-east-asia/.

Government of Canada. 2024. Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy. Ottawa, Canada.

Huebert, Rob. 2009. "United States Arctic Policy: The Reluctant Arctic Power." University of Calgary School of Public Policy Briefing Papers 2 (2): 1-27.

Hunter, Tina. 2017. "Russian Arctic Policy, Petroleum Resources Development and the EU: Cooperation or Coming Conflict?" In The European Union and the Arctic, by Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk and Tore Henriksen, 172-199. Boston: Brill.

Ilulissat Declaration. 2008. "Ilulissat Declaration." www.oceanlaw.org/downloads/arctic/Ilulissat_ Declaration.pdf.

Jervis, Robert. 1978. "Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma." World Politics 30 (2): 176-214.

Killas, Mark. 1987. "The Legality of Canada's Claims to the Waters of its Arctic Archipelago." Ottawa Law Review 19 (1): 95-136.

Kingdom of Denmark. 2011. Strategy for the Arctic 2011. Oslo: Kingdom of Denmark.

Lackenbauer, P. Whitney, and Suzanne Lalonde. 2017. "Searching for Common Ground in Evolving Canadian and EU Arctic Strategies." In The European Union and the Arctic, by Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk and Tore Henriksen, 119-171. Boston: Brill.

Lasserre, Frederic. 2011. "The Geopolitics of Arctic Passages and Continental Shelves." Public Sector Digest.

Norwegian Ministries. 2017. Norway's Arctic Strategy. Norwegian Ministries.

Piskunova, Ekaterina. 2010. "Russia in the Arctic: What's Lurking Behind the Flag?" International Journal 851-864.

Rainwater, Shiloh. 2013. "Race to the North: China's Arctic Strategy and its Implications." Naval War College Review 6 (2): 62-82.

Research, IBRU Centre for Borders. 2016. Maritime Jurisdiction and Boundaries in the Arctic Region: Russian Claims. Accessed November 29, 2018. https://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/ibru/resources/ArcticmapRussianonlyclaims05_08_15.pdf.

Ringborn, Henrik. 2017. "The European Union and Arctic Shipping." In The European Union and the Arctic, by Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk and Tore Henriksen, 239-273. Boston: Brill.

Spohr, Kristina. 2018. "The Scramble for the Arctic." New Statesman 22-27.

The Arctic Institute. 2016. The Arctic Institute. https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/.

U.S. Geological Survey. 2008. Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal. U.S. Department of Energy. htt://energy.usgs.gov.

United Nations. 1982. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. United Nations. http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/UNCLOS-TOC.htm.

U.S. Department of Defense. 2024. 2024 Arctic Strategy. Washington, D.C.: The U.S. Department of Defense.

United States Navy, The. 2014. Arctic Roadmap for 2014 to 2030. Washington, D.C.: The United States Navy.

United States, The. 2009. "Arctic Region Policy." Washington, D.C.

Weber, Steffan, and Iulian Romanyshyn. 2011. "Breaking the Ice: The European Union and the Arctic." International Journal 849-860.

Wegge, Njord. 2011. "The Political Order in the Arctic: Power Structures, Regimes and Influence." Polar Record 47 (241): 165-176.

White House, The. 2013. National Strategy for the Arctic Region. Washington, D.C.: The White House.

ZME Science. 2011. Melting Polar Ice Makes Way for New Shipping Routes. October 5. Accessed November 25, 2018. https://www.zmescience.com/ecology/environmental-issues/melting-polar-ice-makes-way-for-new-shipping-routes/.